Optimizations

Reduce the number of interconnections

In a fully-connected neural network, the number of weights grows O(n2) with a number of nodes. Our network has 1024 nodes per hidden layer, and this is equivalent to one million interconnections in hardware, which is certainly impractical.

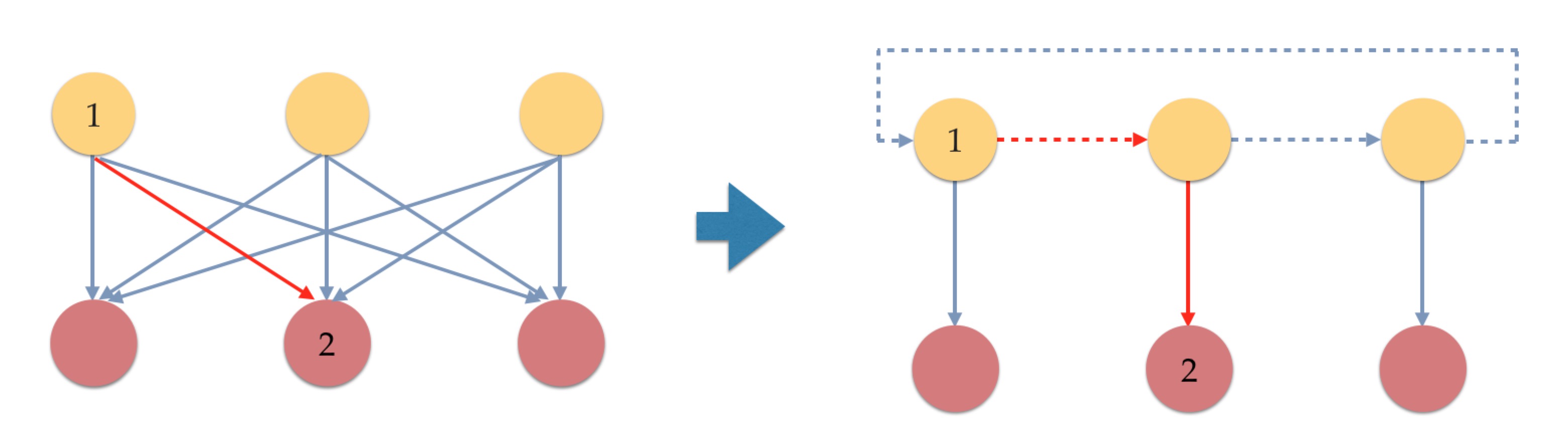

Therefore, we want to reduce the number of interconnections. The intuition is that, instead of using a direct connection between node 1 and node 2 as shown in the left figure of Figure 1, we can use an indirect connection between node 1 and node 2 as in the right figure of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interconnections can be reused if we shift the inputs to proper locations

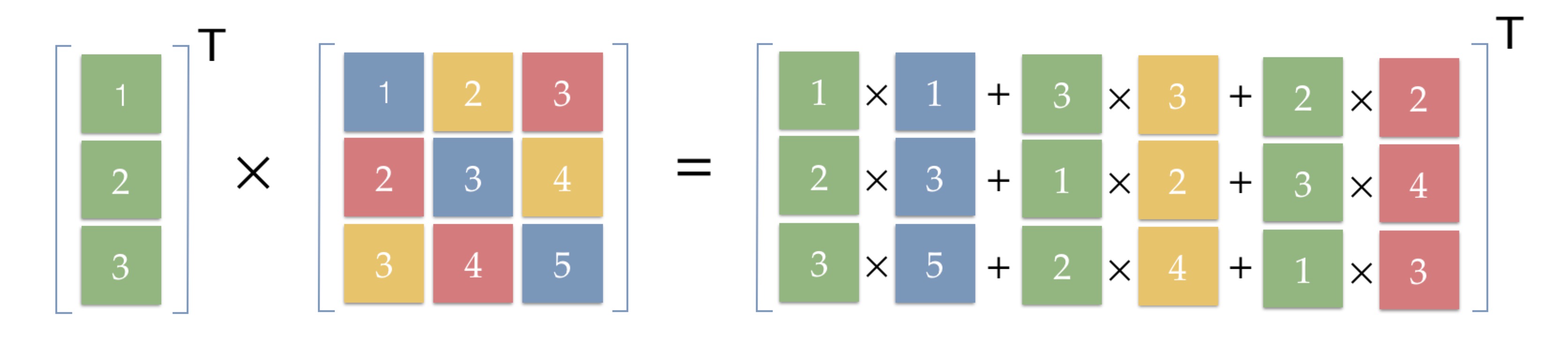

Concretely, one can simply express computation process between two layers with a matrix multiplication operation. Specifically, we first rearrange the contribution of each node due to commutative property as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Interconnections can be reused if we shift the inputs to proper locations

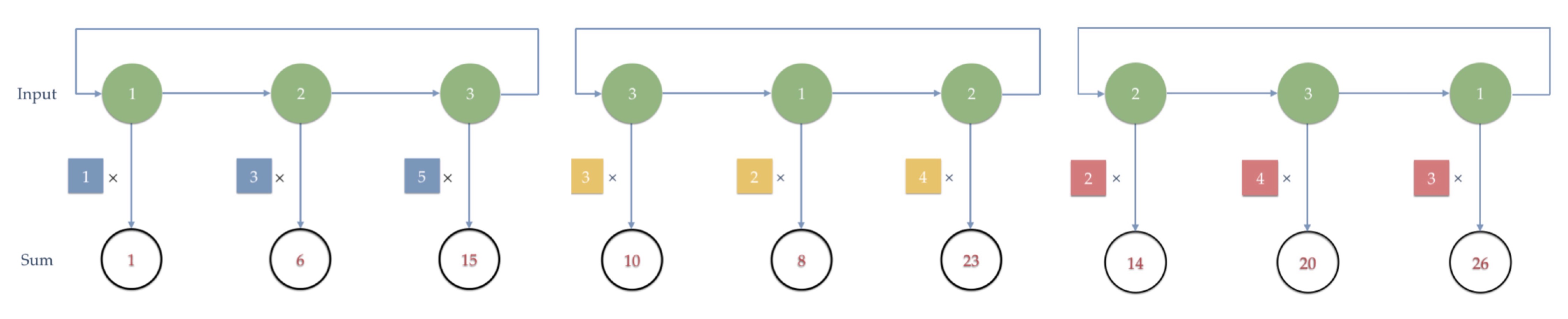

Note that in the result, the first green column is the initial input 1, 2 and 3, and the second green column is a shift of the first column. Also, the third column is a shift of the second column. Based on this updated computation order, we can obtain the final result of multiplication between a vector and an n2 matrix by n iterations as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Neural networks can be partitioned into n2 parts and each part contains only 1/n of the nodes

Therefore, if we rearrange the weights by diagonal, we can use shift and elementwise multiplication instead of matrix multiplication. By this means, we can reduce the interconnections from one million to two thousand for one layer, which is a 500 times saving. Also, the number of interconnections now grows only O(n) instead of O(n2) with the number of nodes, which is much more scalable.

Matrix padding

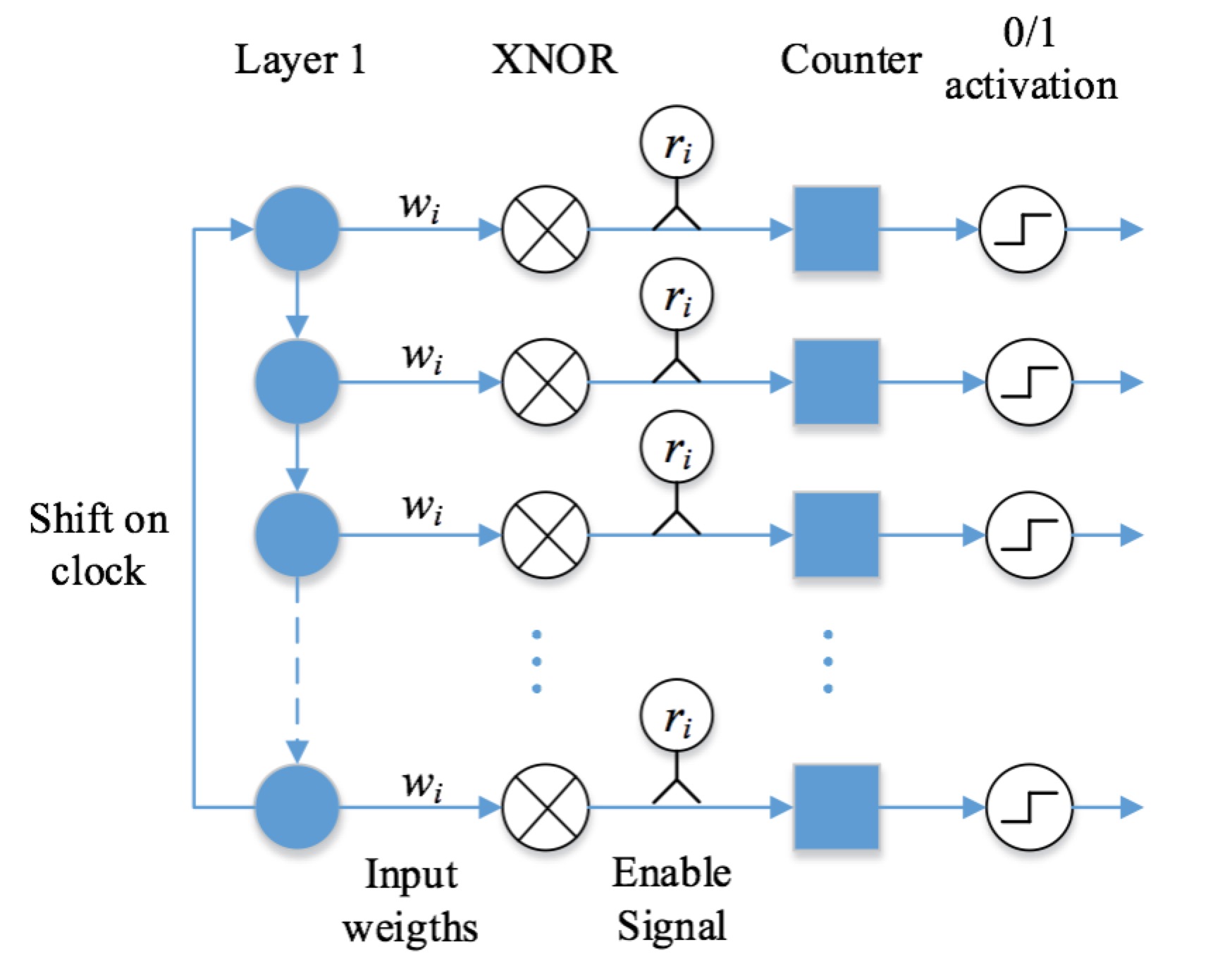

Furthermore, the number of nodes in each layer is usually not the same. For example, we use a 784-1024-1024-1024-10 network. If we use different designs for different layers, it means 4 times more resources, and the resource usage for a deeper network will explode. The idea is to pad matrices that are less than 1024 x 1024 so that all layers can reuse the same hardware module. Considering that we have inactive weights in bitwise neural networks, we can use matrix padding for free. Specifically, an enable signal will decide whether the corresponding weight will count. By this means, we significantly save the hardware resources, in our scenario, by a factor of 4. A drawback is that we potentially may need to load more weights from memory, but the resource savings are more significant.

Batch processing

It turns out that the program is bandwidth bound. To amortize the cost of loading, we can use batch processing. The idea is simple that we copy-and-paste the same module several times until we reach the resource limits. Each module shares the same set of weights from the memory, and therefore the loading cost is amortized.

Implementation

Combining all ideas shown above, the final implementation is illustrated in Figure 4. It accepts binary inputs and gives binary outputs. It also contains XNOR module, enable signal, and bit counter. The activation, which is essentially a comparator, decides whether to activate the output based on the number of ‘1’s.

Figure 4. The hardware implementation of shift and multiplication idea

Evaluation

For evaluation, we target on the digit classification task using the MNIST dataset and all the following experiments are based on the Altera DE2-115 board. The board has 114,480 logic cells, 50 MHz clock and 2 MB SRAM.

In this section, we compare our design with the state-of-the-art approach, and we find that our approach greatly outperforms the state-of-the-art. Note that all measurements are converted to be resource-neural as the related paper tests on a much better FPGA than ours.

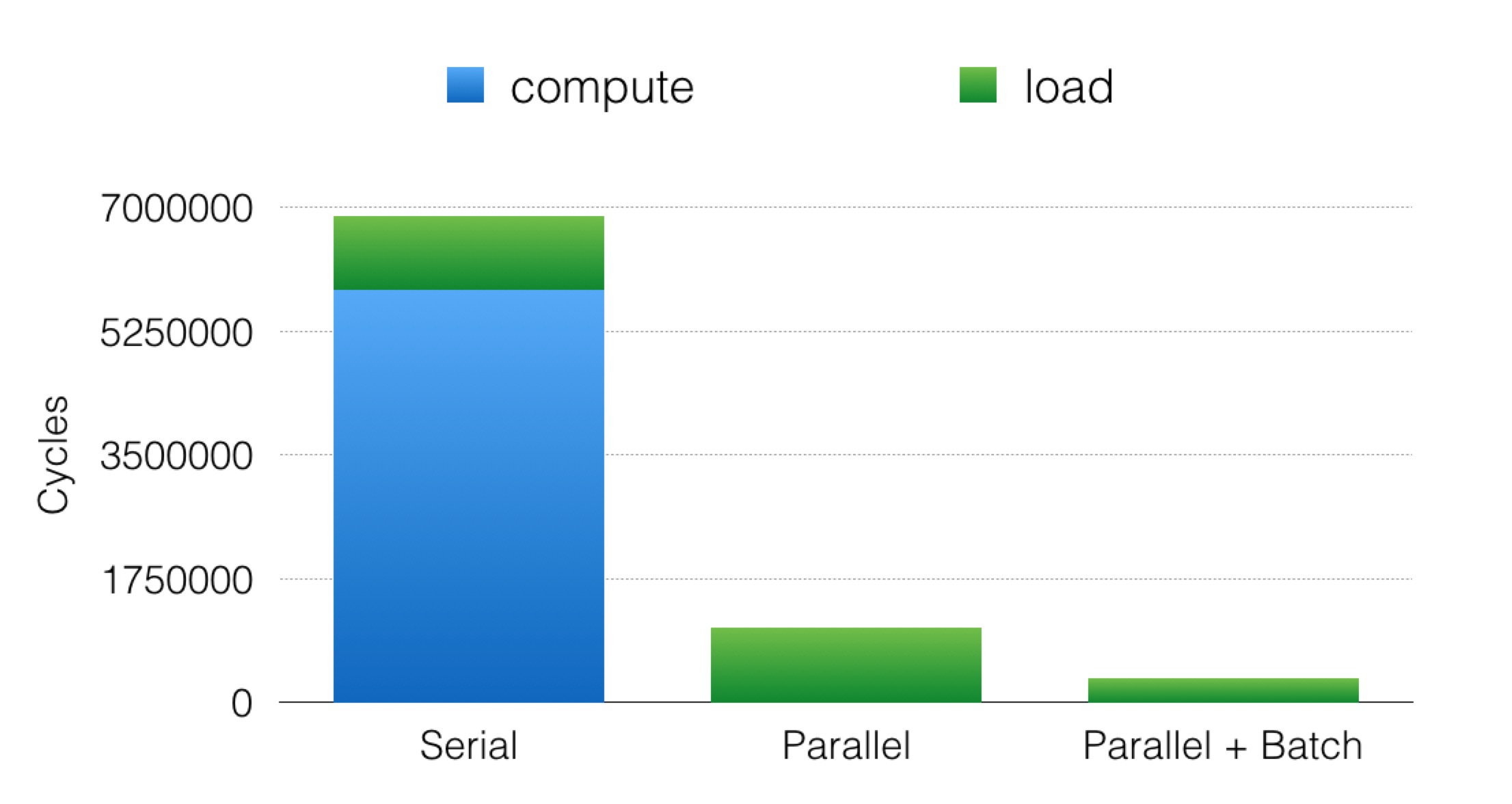

As shown in Figure 5, we speed up the classification phase by 1024x using our parallel algorithm. Compared with the cycles needed for loading weights, it is almost negligible. Then, we further use batch processing schemes to amortize the cost of loading, which reduces the loading cost by three times as we are able to use three modules in our hardware.

Figure 5. The cycles needed for computing drop by a factor of 1024 and the loading cost can be amortized using batch processing

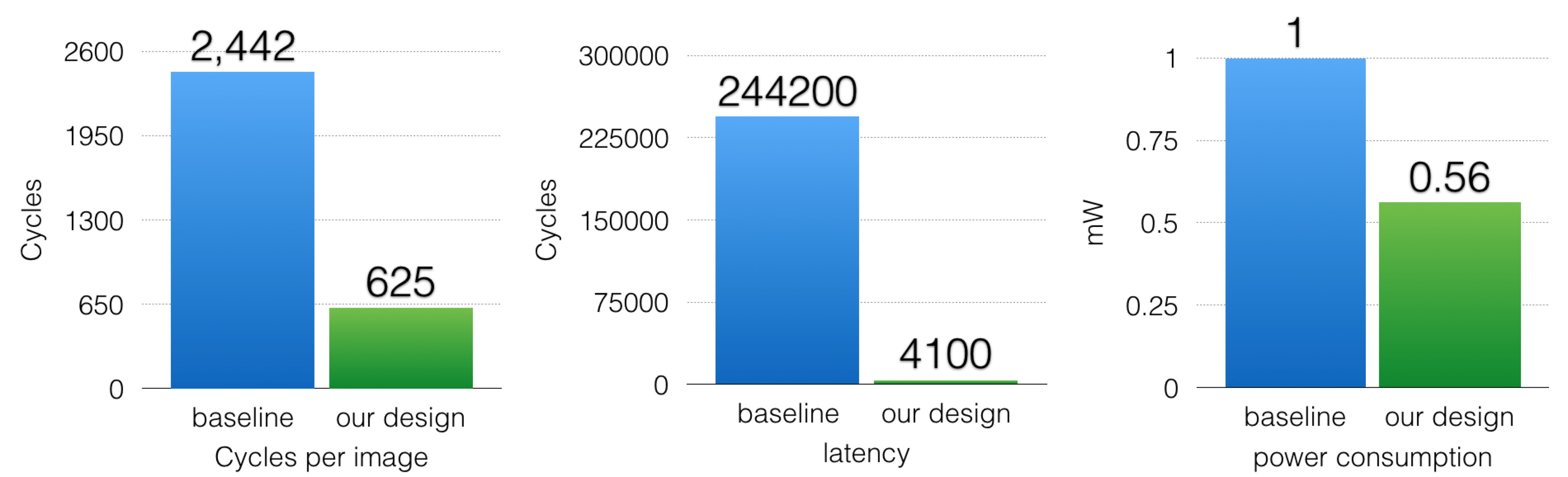

For comparison, we compare our paper with an existing paper that also implements FPGA to classify MNIST dataset. After compensating for the difference in the board, i.e. consider cycles rather than absolute time, our design achieve 4x throughput than [2]. Note that the throughput is normalized by the number of gates, i.e. they use over 210,000 logic cells, while we only use 33,000. Because we can always use batch processing to increase throughput if resources permit. Moreover, our design has a 60 times lower latency than [2], as they use a batch size of 100 to exchange latency for throughput. The real power measurement of [2] is 1 mJ per image, and the Altera power estimator shows our design consumes 0.56 mJ per image. Considering the possibility of under-estimating, the energy consumption could be very similar in the real world. A full comparison is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Comparison of performance between our design and baseline FPGA paper

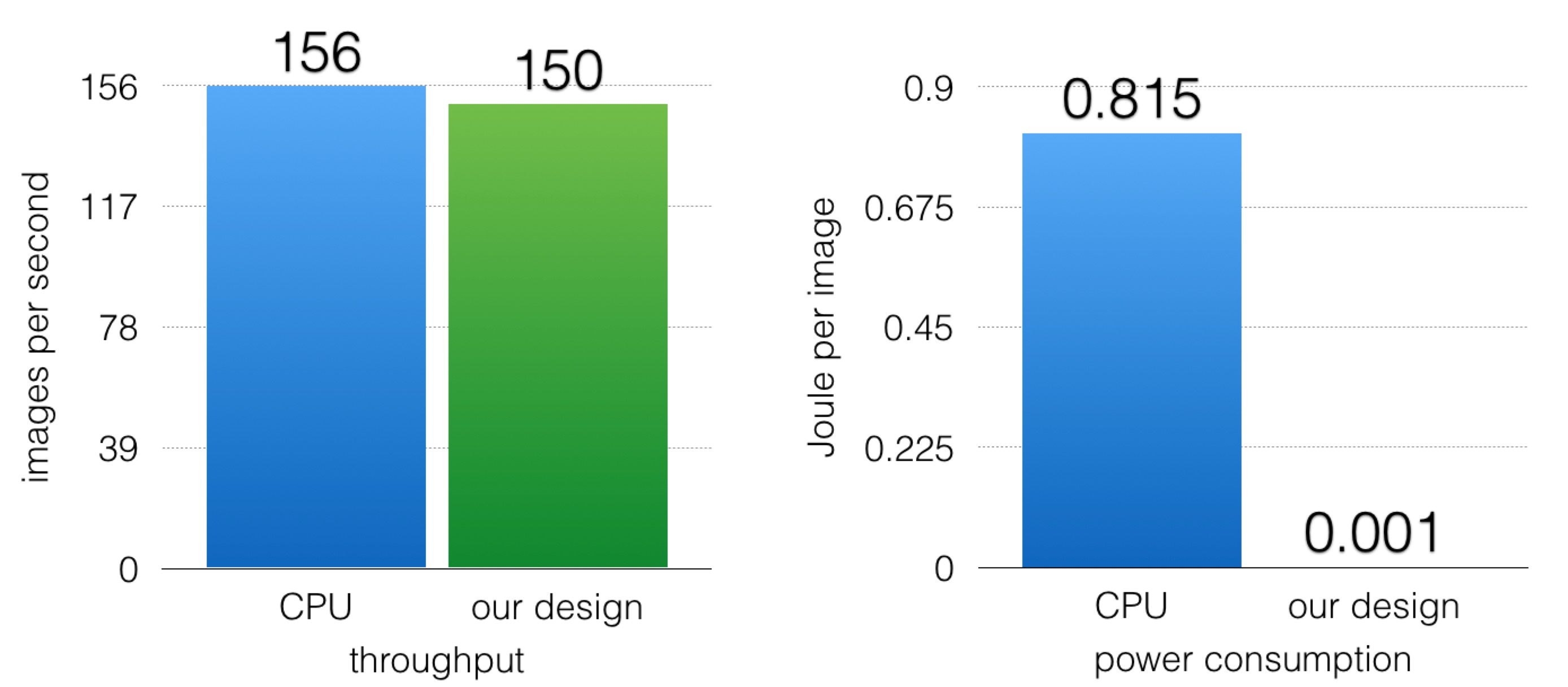

In the second part, we will compare our results with the open source tensorflow design running on a single-threaded CPU, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Comparison of performance between our design and tensorflow on CPU

The CPU has 2.40GHz clock, while our board only has a 50 MHz clock. However, our throughput is very similar to the CPU throughput. Moreover, assuming that the CPU is loaded when executing digit recognition tasks, it will consume 127.1 Watt. Our board consumes 0.16 Watt. Therefore, our energy efficiency is 800 times better than the CPU design.

Conclusions

FPGA implementation of neural networks benefit from higher parallelism, lower energy consumptions and no jitters. Our novel implementation of neural networks have a significant gain over the state-of-the-arts. Also, our design shows the potential of commercial use in more complex tasks.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to 418 staffs for designing this wonderful project and bringing us to this interesting topic, especially Karima for proposing the initial idea. Also, thank Prof. Bill Nace for providing us with the hardware resources.